Engineering has undoubtedly made great advances in civilization. Among its modern marvels are the provision of water and drainage and the construction of buildings and infrastructures that enable social reproduction. However, like all other modern disciplines, engineering is subsumed by the logic of capital. For this reason, as with other disciplines, its application is usually directed towards works that allow for the accumulation, circulation and reproduction of money.

Although this is known, especially among Marxists, it is not usually accepted within each discipline and this is especially the case in the field of engineering. On the contrary, engineering is presented as a technical discipline that has nothing to do with politics. When a development in engineering has a negative social impact, such as facilitating further exploitation of workers or destruction of nature, it is justified on the grounds that it was not the right technical solution, or that the technical solution was only meant to address a specific problem. In other words the presence of class conflict is repressed or ignored.

However, from time to time, criticisms or denunciations of the problems within the disciplines emerge from their own practitioners, as is the recent case of the book “Killed by a Traffic Engineer” (Island Press, 2024), written by engineer Wes Marshall.

This work allows for a critical reading that exposes the ideology behind the discipline of engineering and its consequences for social reproduction: millions of deaths per year. This may not be the author’s intention, but that does little to negate what it makes visible. The book contains a powerful critique of traffic engineering, especially as it is applied in the U.S. Anderson shows that under the banner of «science», the building of road infrastructures that are dangerous – indeed fatal – to users are routinely justified.

All of these decisions are based on studies which present little evidence, often suffer from poor methodologies, or are simply biased because of the ideological drive behind them. This turns this discipline into one based on pseudoscience (p. 5), and as a function of this, manuals and guides are created and blindly followed, becoming entrenched as evidence and justification for a variety of decisions. Marshall writes:

“Despite manuals lacking the requisite science to back them up, traffic engineers put their faith in these manuals and adhere to them. Traffic engineers also don’t take too kindly to those criticizing these holy texts” (p. 33).

To illustrate this, the book makes reference to some of the deficiencies in the fundamental principles of traffic engineering. In the United States. Traffic control manuals stipulate that at least three traffic accidents must occur over a period of four or five years (irrespective of the number of casualties) before the occurrence is deemed a problem (p. 336). If this does happen, the placement of a signalized intersection is authorized. This is irrespective of the context of the intersection, whether it is situated in front of a nursing home, a hospital, or a school, to cite a few examples where pedestrians tend to walk slowly and should therefore be treated as a problem (p. 336).

Traffic engineers assume that as long as vehicles keep a stable distance from each other at a constant speed, there will be no accidents. At the same time, speed limits must be constantly adjusted to the speed of 85% of vehicles (p. 162). This is done to ensure the free flow of traffic and to maintain a stable distance between vehicles, as congestion is supposed to cause traffic accidents. When these ‘technical principles’ are applied to a real case, the situation can be tragic. In one case, a 60-year-old woman was killed in Los Angeles (USA), when a few months earlier a 19-year-old man had been hit while crossing the same street. After the first incident, the local authority decided to carry out a speed analysis (based on traffic engineering) and, based on the above «scientific principles», increased the speed on the street where the hit-and-run occurred. The study showed that 68% of the vehicles on the marked road were travelling at 35 mph, so they decided to increase the speed to 40 mph. Over the next decade, fatalities continued to occur, and they continued to increase the speed limit, first to 45 mph and then to 50 mph (pp 153-154). It does not take an engineering degree to see the contradiction: higher speeds only increase the vulnerability of pedestrians, but the manuals called for higher speeds to provide greater ‘safety’.

Another interesting exampls is that in the construction of dams, bridges, buildings and other similar infrastructures, the «design load» is a key consideration, i.e. the physical forces that these structures can withstand so that they can withstand extreme events and not collapse under weight, tremors or other external forces. The same concept is then applied to traffic engineering (p. 156) as «speed design». In civil engineering, it is desirable for the design load to be greater than the maximum possible load, as this makes buildings safer. In traffic engineering, higher speed designs result in wider roads with fewer intersections, more bridges and tunnels, etc. However, unlike built structures, when a road receives more vehicles than its ‘design capacity’ can handle, it does not collapse or fail. It simply becomes congested, which increases travel times, but does not result in tragedy. This concept has been used to justify the widening of roads, the construction of bridges and tunnels and other road solutions in the face of increased traffic (below design speed). However, it has been shown that more road infrastructure only induces more traffic and congestion and makes the road more dangerous.[1]

When this criticism comes from an engineer, it acquires greater power. Wes Marshall recognizes that there is a systemic problem and suggests that traffic engineering should be re-engineered to improve road safety (p.5). A noble and necessary goal, no doubt. However, he does not go deeply enough into the causes that have led to this situation, nor into the objectives of his critique.

Let’s start with the question: why does road construction and its relationship with vehicles exist in the first place? The answer is that roads and cars exist because of the development of capitalism and the creation of the combustion car as a commodity for mass consumption.

Capitalism has subsumed science to create commodities of all kinds and purposes. One of the most successful examples is the automobile, whose production and consumption have allowed a great accumulation and reproduction of capital since its invention. As well as other industrial and financial capitals that revolve around the automobile: construction, transport, finance, insurance, etc.

In order to allow vehicles to be sold by the thousands and to occupy urban space with great «freedom» (impunity), in addition to the appropriation of the common space for the construction of thousands of miles of roads dedicated to them, something had to be done to order and regulate them. Without regulation, they could pose a problem for other economic activities and for the sale of cars. This implies the transformation of the common space (the streets) in favor of these goods.

In this sense, this discipline follows the logic of capital and ignores social reproduction. Although in both cases the circulation of goods, services and people by different means of transport is necessary, the primacy of the automobile as a commodity within capitalism is in conflict with the other function of the automobile as a means of transportation.

Traffic engineering tries to create a balance between them, but it is impossible. There is a fundamental contradiction between the functions of cars which, under capitalism, is usually resolved in favor of capital (and therefore in favor of speed). As Marx pointed out, capital seeks to «the annihilation of space by time», with the aim of accelerating the process of circulation of capital and ensuring its reproduction.

Therefore, under this mandate of capital, traffic engineering is ideologized to hide this contradiction, which cannot be resolved within capitalism. Here are some examples from the book to illustrate this. Technically, there is nothing to stop the speed of cars being limited from the moment they are manufactured, but this is not done. When the first cars were on the road, some local authorities wanted to do this because they considered the speed limits to be dangerous for the public. However, the car companies fought against the possibility of such speed limits being legislated and won (p. 55). It is now taken for granted that cars can exceed the speed limit. This has carried over into road design and the implementation of limits, where traffic engineers try to encourage vehicles to travel as fast as possible. Socially, vehicle performance is no longer questioned and speed limits are rarely proposed to be reduced. The argument is that the higher the speed, the shorter the transfer times (of goods and labor) and the less congestion. This is despite evidence that travel times and congestion have changed little over the last 100 years (p. 103).

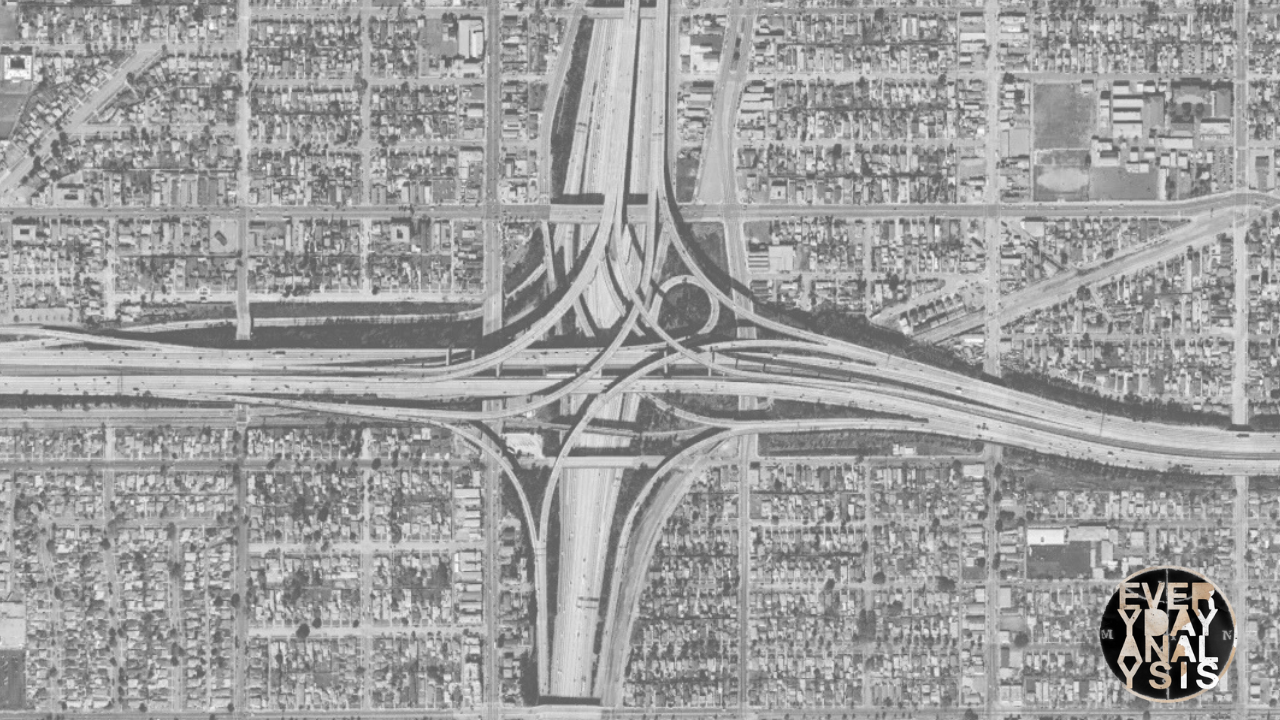

In addition, the construction of highways and the maintenance of high speeds have often been justified by the idea (and fear) that high traffic volumes will «kill» the economy. This has led to the creation of high-speed roads within cities, affecting poor or racialized communities under the guise of «revitalizing» these areas. What James Baldwin called «Urban Renewal Means Negro Removal”[2]. Infrastructure projects carried out under the ideology of capital with real negative effects on the working class.

For example, the 1957 American Association of State Highway Officials (AASHO) manual states:

“Most cities have blighted areas slated for redevelopment. Where they are near general desire lines of travel, arterial routes might be located through them in coordination with slum clearance and redevelopment programs” (p. 222).

Or the traffic engineering journal Traffic Quarterly in 1953, which described urban freeways as a good way to eliminate slums:

«In each case, the highway locator has an opportunity to assist the community in the redevelopment of depressed areas and to open up for good development other areas not otherwise progressing…removal of low tax paying properties and development of high tax properties have helped measurably to solve difficult city revenue problems” (p. 222)

This is not only a class struggle in which capital expropriates from the workers their common and fundamental space for social reproduction but is also largely linked to the dominant logic of capital in each country and city.

Another good example of this is the road classification established by traffic engineering in the United States. The local, collector, and arterial classification attempts to standardize all roads, especially arterials with wide lanes, no intersections, and high speeds. It assumes that they have a high level of motor vehicle and traffic mobility and little access to surrounding land. “This approach aims traffic engineers toward a certain target, and that target is a tree-like street network” (p.209). This is a type of classification that does not consider rural or urban.

This seemingly innocuous classification by function reproduces a dominant model of capital accumulation. In this case, that of road and highway builders, including urban ones, as well as real estate developers engaged in suburban housing construction. On the one hand, it favors the public financing of what are considered the most important roads (roads, highways and arterial roads, p. 271), leaving aside the financing of public transport. On the other hand, it favors suburban developers, perpetuating automobile dependency. Anderson rightly points out that «Functional classification helped make American built environment -especially the thousands of square miles of new suburbs – family and almost permanently oriented to automobiles” (p. 212). Harvey (2010) has pointed out that this form of urban expansion was fundamental to the absorption of labor and capital surpluses in the postwar United States, and the spread of automobile culture in particular has allowed this process to spread globally.

In addition, the construction of roads and highways was so ideologized that it used the rhetoric of a possible nuclear war with the USSR to its advantage (p. 218). The roads would serve to evacuate the population from the cities in the event of a conflict with the Communist bloc. And paradoxically, they made it possible to weaken the workers’ movement, since it allowed the delocalization of industries to the suburbs and to the south in U.S. and the creation of suburbs thar increased alienation, individualism, consumerism and automobile dependency among workers, and was a counterrevolutionary tool that fragmented communities and working-class neighborhoods.[3]

Another example is the idea of «engineering judgment,»[4] i.e., that only engineers are qualified to propose or make road improvements because the rest are incapable. Undoubtedly, this idea of professional «common sense» is a clear statement of how they seek to perpetuate a way of thinking without outside criticism. Common sense is nothing more than the idea and social rules of the status quo, which is not and cannot be revolutionary.

Many liberal and progressive groups often underestimate the power of capitalist ideology. In many cases, these groups believe that it is possible to «progressively» reform the biases of various disciplines. However, many disciplines are highly intertwined with the logic of capital, so they are highly ideologically charged, which is not harmless and has consequences. It contributes to the construction of the “systemic violence that is inherent in the social conditions of global capitalism, which involve the automatic creation of excluded and dispensable individuals from de homeless to the unemployed” (Žižek, 2008). In the case of traffic engineering, it has not only allowed the expropriation of common resources in favor of car companies, but also causes thousands of deaths a year with impunity. Ideology kills.

References

- Cervero, R., & Hansen, M. (2002). “Induced Travel Demand and Induced Road Investment: A Simultaneous Equation Analysis”. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy, 36(3), 469–490. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20053915

- David, Harvey. (2010). The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Davis, Mike. (2018). Prisoners of the American Dream. Politics and the Economy in the History of the U.S. Working Class. London: Verso.

- Duranton, Gilles, and Matthew A. Turner. 2011. «The Fundamental Law of Road Congestion: Evidence from US Cities.» American Economic Review, 101 (6): 2616–52. DOI: 10.1257/aer.101.6.2616

- Marshall, Wes. (2024). Killed by a Traffic Engineer. Shattering the Delusion that Science Underlies Our Transportation System. Washington: Island Press.

- Karl. (s. f.), “Exchange of Labour for Labour Rests on the Worker’s Propertylessness”, Grundrisse: Notebook V – The Chapter on Capital, Marx Engels Archive, recuperado en abril de 2021, de <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/ch10.htm>.

- S. Pirg Education Fund. (2004). More Highways, More Pollution. Road-Building and Air Pollution in America’s Cities. U. S. PIRG Education Fund, Washington.

- Žižek, Slavoj. (2008). New York: Picador.

[1] There are several statistical and econometric studies that demonstrate the phenomenon of induced traffic. To cite some of the most relevant: Cervero, & Hansen 2002; US Pirg Education Fund, 2004 and Duranton, 2011.

[2] Urban Renewal…Means Negro Removal. ~ James Baldwin (1963). Retrieved December 3, 2024, from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T8Abhj17kYU

[3] Mike Davis (2018, pp. 140-142) points out that there were two trends that restructured the U.S. industrial economy and weakened the labor movement: the strategy of deindustrialization and relocation to the periphery and the southeastern United States. To places where unions did not exist or had little representation, allowing downward pressure on union wages. This was only possible thanks to the creation of U.S. interstate highways, which made it possible to create the production conditions for this.

[4] “Engineering judgment shall be exercised by a professional engineer … with appropriate traffic engineering expertise, or by an individual working under supervision of such an engineer, through the application of procedures and criteria established by the engineer” (p. 313).

Publicado originalmente en Everyday Analysis